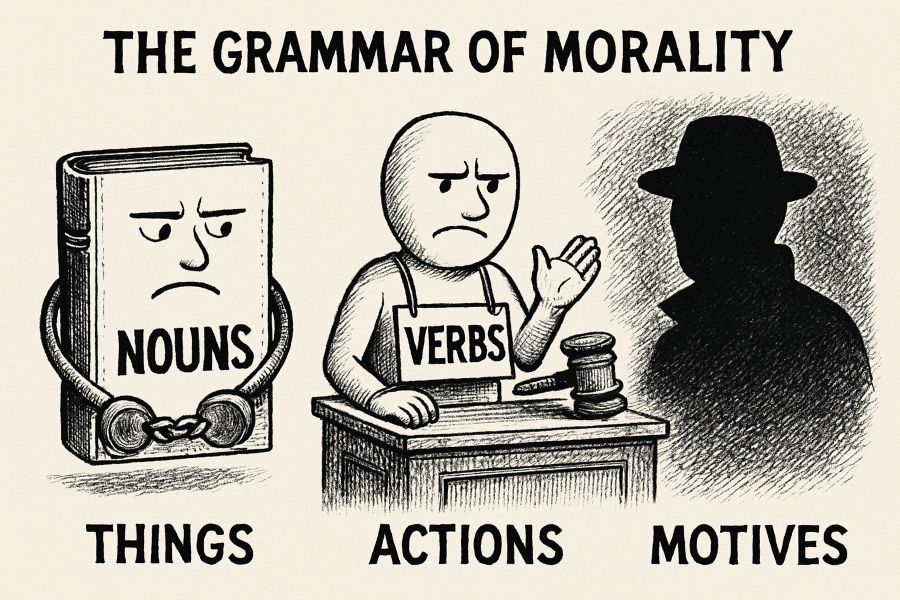

The Grammar of Morality

We often equate morality with subtraction—removing objects to reveal virtue. But things gain meaning through use, and actions through context. The real mistake is confusing what’s visible with what truly matters.

People often begin their moral education by fixating on things—nouns like alcohol, guns, rock and roll, or pictures of naked women. It’s easy to point at these objects and say, “Ban them, and the world will be better.”

Some evolve from this noun-based morality to one focused on actions—verbs like drinking, playing, firing, or looking. The logic shifts: outlaw the deed, not the object.

Further down the road, a few stumble into the realm of motives. Here, the question becomes not what you do, but why you do it. And this is where things get interesting—because even good deeds can be done for terrible reasons, and even “bad” actions may stem from harmless intent.

(I place myself in this school of thought. To everything there is a season. It’s not what you do—it’s why you do it.)

Now, some might be thinking I’m just looking for an excuse to drink heavily while shooting pigeons under the influence of heavy metal and pornography.

But all this is to say: it’s easy to blame things and actions, and to measure people by them. Motive and reason—often invisible—are a far better measure. And that makes judgment a much trickier business.

Sure, some people should abstain from certain things. Know thyself. But others wouldn’t be better off if they did. It’s not the deed that misses the mark—it’s the thought behind it.

Harry is a recovering satirist, part-time philosopher, and metadata tinkerer. His archive spans two decades of metaphysical mischief, theological punchlines, and poetic nonsense. He believes in satire’s transformative power, the elegance of expressive metadata, and recursion—once writing a poem that never ended and a script that crashed browsers.

This reframes morality as a layered progression—objects, actions, then motives—showing how judgment grows trickier the deeper you go. I especially like the reminder that intent can invert the moral weight of a deed, turning virtue into vice or vice into something harmless. It’s a sharp critique of surface-level morality, and the humor about pigeons and heavy metal keeps it grounded in human absurdity.